“It’s all about the detail, the focus, the ability to freely channel artistic expression through meticulous mastery of craft technique. Fundamentally, there is little difference in approach between embroidery and writing. The same applies to the culinary arts, or painting – if you want to do something well, you need to balance art and craft in a union of head, hand, and heart.“

– Leon Conrad

A multi-award-winning author, academic, playwright, poet, educationalist, storyteller, and polymath, Leon Conrad embodies the boundless potential of a curious mind. Through a kaleidoscope of pursuits spanning from literary endeavours to historic needlework, he weaves art, craft, and academia with expressed dedication and a profound appreciation for detail.

Leon Conrad’s artistic odyssey is as diverse as it is enthralling. Invited as the poet-in-residence at the inaugural Edinburgh Food Festival in 2006, Conrad’s poetic prowess found expression in the culinary realm, bridging the gap between gastronomy and verse. His literary contributions encompass a wide spectrum, ranging from the comprehensive guide on storytelling and structure in the BREW Seal of Excellence award winner and People’s Book Prize nominee, “Story and Structure: A Complete Guide,” to the whimsical world of versified fables in “Aesop the Storyteller.”

Beyond the written word, Conrad’s creativity extends to the stage, where his plays, such as “Aesop the Storyteller” and “Under the Arabian Moon,” enchant audiences with their timeless resonance. A true polymath, Conrad’s expertise in historic needlework adds yet another layer to his multifaceted persona. Rediscovering intricate embroidery stitches lost to time, his contributions to the preservation of cultural heritage are as meticulous as they are invaluable.

As an academic, Conrad’s insatiable curiosity leads him down pathways less trodden. From unraveling the vagaries of the English language for Anglophile Russian travelers to tackling the nuances of 16th and 17th-century woven and embroidered textile bookbindings, his scholarly pursuits know no bounds. A reflection of his dedication, Conrad’s exploration of George Spencer-Brown’s Laws of Form not only shaped his understanding of logic but also revolutionised his approach to analysing story structure.

In conversation with Conrad, one is drawn into a world where storytelling becomes a sacred art, weaving together threads of tradition and innovation with seamless grace. His commitment to preserving oral traditions and integrating classical liberal arts education into modern pedagogy speaks volumes about his reverence for the past and vision for the future.

Through this exclusive interview, let him take us to a world of discovery, where history and imagination converge towards boundless possibility.

Early Influences and Education

TWB: Can you share with us some of the key experiences from your upbringing in London and Alexandria, Egypt, and how they have influenced your creative journey?

LC: I’m sure many people remember being told stories or having story books read out loud to them as children. Those warm, cuddly times when I was transported to the land of story when my mother read me a bedtime story are still part of me. I particularly enjoyed poetry, and the playful use of language in stories like ‘The Cat in the Hat’.

But it was when I was growing up in Egypt that I first fell in love with stories and storytelling. On two unforgettable occasions, I heard an oral storyteller from a living Arabian Nights tradition tell an improvised story to a group of rowdy schoolchildren. She kept us all spellbound.

That impressed me.

She got my attention.

When she stopped, I knew I’d found a vocation – I wanted to find out the secret of the power she had to keep us spellbound. I’ve learned a lot along the way – about voice, variety, pace, characterisation, drama, suspense, surprise.

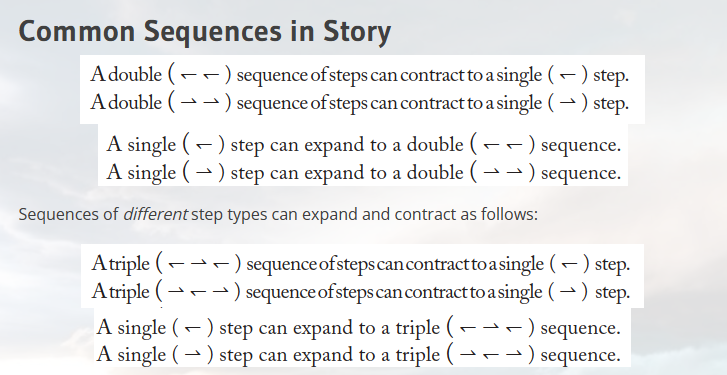

There’s still so much to learn about language, poetry, and the deep structures of story – something I’ve written about in detail in my book, Story and Structure which outlines how people can use six basic simple symbols to structure and write stories that ‘go with the flow of story’ by working at that deep level.

When you use story structures that have lasted centuries, that emerge in us naturally in response to different types of problems; when a character’s story line follows a story structure that is perfectly suited to the kind of problem it is meant to solve, you will be telling stories that flow naturally.

A storyteller colleague of mine calls it ‘following the grain of the brain’. I’d go a step further. For me, choosing the right story structure will ensure your stories flow more smoothly because they ‘follow the goal of the soul’.

“The threads of song, the magic of melody, the beat of a strong rhythm, and the romantic ways in which concord and discord flirt, and tease, and dance are things that continue to inspire me as a writer.”

– Leon Conrad

TWB: How did your early involvement in music and theater shape your approach to storytelling and artistic expression?

LC: The threads of song, the magic of melody, the beat of a strong rhythm, and the romantic ways in which concord and discord flirt, and tease, and dance are things that continue to inspire me as a writer.

And to inspire others, I have included quite a few games that encourage writers to play with sounds and rhythms in a new book, Master the Art and Craft of Writing: 150+ fun games to liberate creativity. Here’s an example. I call the game ‘Word tango: forming the sound fantastic’.

Take a tango. Listen to the track once. Feel the rhythms. Feel the phrases of the melodic lines. Play it back and write something inspired by – but not a direct reproduction of – the rhythm of the piece.

Reflect on the result. What worked? What didn’t work? How can you use what you learned to make your writing dance in your reader’s ears?

A Career Journey

TWB: From studying piano and voice to becoming a writer, educator, and specialist in historical needlework techniques, what pivotal moments or decisions led you to pursue such a diverse range of interests and professions?

LC: What can I say? I just love challenges. And I also love trying to find satisfactory answers to questions we don’t yet have satisfactory answers to. Sometimes the spark results from coming across something unexpectedly: I was 12 or 13 when I heard a singer whose deep, haunting, rich, contralto voice soared in an arc of magical melody above a choir. The experience was unforgettable. It touched something very deep within me, and set me on a lifelong quest to find out how it is that the human voice can have such a profound effect on someone. Sometimes the spark comes from meeting an expert in a given field. I was extremely fortunate to be taught blackwork embroidery by one of the greatest practitioners of the craft, Jack Robinson. And I could never have uncovered the hidden story of story which I write about in Story and Structure had I not been lucky enough to meet George Spencer-Brown. The six simple symbols I use to map story structure are drawn from his ground-breaking book, Laws of Form. Many works on mathematics and logic that I’ve read I’ve found largely dry, dull, and boring. His work was different. It is pithy, vibrant, and I found it full of life. I was his last student. He took me through the work step by step. As others have found, Laws of Form is a gift that keeps on giving. I try to run a couple of live online courses every year related to Laws of Form, one covers its use in logic; the other covers its application to story structure which is aimed at writers, storytellers, narrative therapists, professionals who apply story-based techniques in their working lives, and members of the general public who are interested in story and want to find out more about how it works.

TWB: How do you believe your varied background has enriched your perspective as a writer and educator?

LC: On the surface of things, if you look at the various fields I’ve explored: historic needlework; voice training, public speaking, performance poetry; story structure, and quite a few more, you’ll probably be puzzled as to what they might have in common. But there is a common element. It’s hidden in plain sight. When I engage in counted thread embroidery, I work in and out of the holes framed by the intersections of fabric threads. That is where the meaning lies. When I work with voice, I focus on the silence from which sound resonates and deep thought emerges, which again, is where meaning is found. And when I work with story, I connect to a deep element of balance that lies at the heart of story. As I outline in Story and Structure, stories generally arise out of a perceived imbalance, and their purpose is to show us (directly or indirectly) how important it is to maintain a sense of balance and harmony in what we do. This is one of things I aim to evoke in writers in the writing classes I teach for children and adults online and in person.

“As I outline in Story and Structure, stories generally arise out of a perceived imbalance, and their purpose is to show us (directly or indirectly) how important it is to maintain a sense of balance and harmony in what we do.”

– Leon Conrad

Expertise in Historic Needlework

TWB: Can you tell us more about your apprenticeship with master embroiderer Jack Robinson and your MA degree in the History of Design and Material Culture of the Renaissance?

LC: Jack Robinson was a true master of the art of blackwork embroidery. He had worked as an engineer and in the police force and took up embroidery as a hobby when he retired. His love of historic needlework led him to try to reproduce challenging designs from the past, including book pillows, embroidered book covers, workboxes, a coif (a type of bonnet that Elizabethan women wore at hom), and samplers. His work is found in museums and private collections around the world. Jack published two books on blackwork embroidery, both of which are excellent. Only one had been published when I first found out about his work, and it was because of that book that I contacted him to ask whether I could take lessons with him. As a true master, he sent me a test piece to work on so I could demonstrate my skill level, based on which he would either take me on or send me on my way. You know what it’s like waiting for exam results! This was twenty times worse. It was two weeks before a hand-addressed envelope in his handwriting arrived through the letterbox. Opening it, I saw the letter had several pages to it. Was this good news or bad, I thought? Either way, I thought, he had been generous enough to share his opinion and give me feedback. I was keen to learn, but I thought I’d better sit down before reading through it. When I read through the letter, his comments were thorough, detailed, insightful, and technically extremely valuable. What’s more, they were remarkably positive. It was the beginning of an apprenticeship which lasted a number of years, and led to a deep and respectful friendship. Most of what he taught me was not communicated in words. It was tacit knowledge passed down through a process of learning-in-action, in an age-old tradition of craft mastery. He really knew his stuff, and I was lucky to know him.

As a result of working with him, I became more and more interested in the culture in which blackwork embroidery pieces had been produced. We see the work on clothing; we see the techniques on samplers, but we rarely see it on bookbindings, or interior furnishings. I wondered why. When I applied to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) and Royal College of Art (RCA) master’s degree to study the History of Design and Material Culture of the Renaissance, I intended to focus on blackwork embroidery. I ended up being sidetracked by illustrations of Aesopic fables, and I got seduced by the beauty of embroidered bookbindings. I ended up rewriting the history of the latter and was inspired by the story of Aesop’s life – an ongoing interest. I have recently brought out a second edition of my collection of versified fables: Aesop the Storyteller which came directly out of my time on the V&A/RCA course.

TWB: What drives your passion for preserving and reviving traditional embroidery techniques, and how does it intersect with your other creative pursuits?

LC: I have little time to do embroidery myself now, but I will teach or mentor if asked to, as I am committed to pass on my knowledge and keep traditional skills alive should suitable opportunities present themselves. I still have a research project in me relating to 17th century embroidered picture designs and the pattern drawers who produced them. These pictures tell complex stories, and I love the idea of exploring these and rediscovering and communicating not only the stories depicted in the designs, but also the stories of the people who drew and worked them, in the complex context of the religious and political tensions of the time, something I wrote about in my MA Thesis, A Veil of Mystery: English 16th and 17th Century Woven and Embroidered Bookbindings and continue to lecture and speak on when invited to do so.

So far, the achievement I’m most proud of is having been the first person in around 400 years to correctly decode how the complex embroidery stitch known as plaited braid stitch was worked. I went on to discover several attractive variations on the stitch and published the results in two issues of the Historic Needlework Guild of America’s Fine Lines magazine. As the articles are now out of print, at some point, I plan to publish a revised edition so people can have access to this work.

Artistic Endeavors and Exhibitions

TWB: Could you share some memorable experiences from your involvement with The New Elizabethans Embroidery Group and your participation in exhibitions and seminars?

LC: My generation grew up without computers. I produced early written work on a typewriter and my graduate thesis on a word processor. When the Internet appeared in the early nineties, people all over the world who shared common interests were able to connect easily in a way which had not been possible previously. It was through the Compuserve Fibercrafts Forum (now no longer active) that I met Linn Skinner, a fellow enthusiast of historic needlework, who encouraged me to develop my work commercially. She was not only motivated me to set up Leon Conrad Designs and publish my embroidery designs, which you can still find on Etsy, but also to put my work into group exhibitions where I won a few prizes. While much of the focus in the 1990s and 2000s was on contemporary embroidery, we wanted to focus on traditional techniques. The New Elizabethans Embroidery Group came out of that. Apart from Linn Skinner and myself, members included US-based traditional embroiderer and designer Sharon Cohen, who ran The Nostalgic Needle, Barbara Fitch, an expert in straw work and straw embroidery, and Meike who was an expert in colifichet, a little-known technique of embroidering on paper. She did use a Singer treadle sewing machine, but we made an exception for her. She produced embroidered cuboards, embroidered wallpaper and some stunning sculptural pieces. We supported each other creatively, put on a number of exhibitions at The Museum of Garden History in London and at Tudor houses around the UK, sold quite a few works and were commissioned to create others, the last group show was in 2004, after which the group was disbanded.

TWB: How do you balance your roles as an artist and educator in these settings, and what do you hope to convey through your artistic endeavors?

LC: Demonstrations and workshops were always a key part of The New Elizabethans Embroidery Group shows, as were tactile and sensory items on display for people to touch. You can only really appreciate the level of detail and the focus required to produce top quality artwork if you have direct experience of it yourself. It’s all about the detail, the focus, the ability to freely channel artistic expression through meticulous mastery of craft technique. Fundamentally, there is little difference in approach between embroidery and writing. The same applies to the culinary arts, or painting – if you want to do something well, you need to balance art and craft in a union of head, hand, and heart.

I have learned much that has fed my practice in all of the above areas from practising traditional geometry which continues to inspire me.

And, of course, the activity has to be a source of joy. If you feel joy in what you do, then you are far more likely to communicate that joy to others.

Yes, it’s hard work – but that doesn’t mean it need to be enjoyable – hence my focus on a playful approach to learning, which is at the heart of the Odyssey Grid experience (Odyssey: Dynamic Learning Journey), History Riddles and the writing games outlined in Master the Art and Craft of Writing.

Contribution to the Performing Arts

TWB: As Poet-in-Residence at the First Edinburgh Food Festival and the Pleasance Theatre, how do you infuse poetry and creativity into your performances and reviews of fringe theater?

LC: I find a social space in poetry. And when I get the chance, performance poetry enables me to share my work with others. In my residencies, serendipity continually provided inspiration: people sitting in the Pleasance cafe, shows I saw, events I witnessed all supplied me with ideas. I once created poems on bananas which we displayed and sold at market stalls we ran as pop-up fruit and veg stalls; When inspiration came from people-watching, poems flowed. I gave the works to them. The space that I curated was a space where people had the chance to write a poem that they’d enter in a daily competition. It was fun! And yes, I use poetic patterns when I write. You’ll find that some of my reviews had hidden Easter Eggs in them. It was a game I played to entertain myself. Do I still do it? Maybe I do. What about you?

TWB: What unique perspectives do you bring to your role as a critic, and how does it influence your own creative endeavors?

LC: Criticism is an art. The 19th century critic John Gibson Lockhart published a damning verdict about Dickens’ work, stating that ‘he has risen like a rocket and he will come down like a stick,’ Shortly afterwards, he and Dickens met. Dickens’ response was, ‘I will watch for that stick, Mr Lockhart, and when it comes down, I will break it across your back.’ The best criticism is constructive, not destructive. When writing reviews, I followed a strict process: I automatically gave a show 3 starts out of 5. The effort it takes to put on a show deserves to be recognised. If there was clear character development; if I was moved emotionally, the show got 4 stars. If the experience was innovative, transcendent, sublime, that’s when the 5-star reviews kicked in. If there were technical problems, those reduced the 3-star rating by 1 star, and if the show had nothing to commend it, the review was not published. Sometimes, on very rare occasions, if I felt a show was bordering on a 5-star review, I would pass on feedback and go again, and publish the review based on the second show I attended.

But I stayed to the end. As a reviewer, you have to give people a chance.

You only buy the right to leave a show after it’s started if you have bought a ticket. If you are there to review it, then however, bad the show is, you are duty bound to stay to the end. I apply the same criteria to my work as a writer and a publisher. I aim to produce high-quality work. I work with designers and illustrators whose work I admire. I aim for 5-star + products. I’m glad to say that so far, it’s worked out. Story and Structure has won over 10 literary awards, and I’m grateful to the BREW awards for one of the best reviews I’ve had for the book: artfully critical, well-written, and very constructive.

Contribution to Education and Tutoring

TWB: As a lecturer in Musical Theatre and a specialist in tutoring gifted and twice exceptional students, what guiding principles inform your approach to education and mentoring?

LC: There are two basic groundrules I set: Get the basics right. Aim for the stars.

I love meeting people years after I’ve taught them and finding out how they’ve got on.

Very often they will say, “It was fun.” They also say that what they learned was useful. One ex-student I bumped into recently said, “I still use the techniques you taught me – I’ve used them through my university degree, and I still use them at work.”

I don’t just help students acquire techniques to pass exams; I aim to equip them with techniques for life.

And that involves bringing in experience and knowledge of voice use, rhetoric and oratory, and music. How else can you teach others to harmonise themselves?

“I don’t just help students acquire techniques to pass exams; I aim to equip them with techniques for life.”

– Leon Conrad

TWB: How do you draw inspiration from classical Liberal Arts education to nurture creativity and critical thinking in your students?

LC: Too many people teach to the test. It’s nothing new. It’s been going on since classical times.

For Seneca the Younger, writing to the Procurator of Sicily in the 1st Century AD, the integrative quality was key. In his ‘Moral Letters’, he wrote that ‘liberal studies’, had nothing to do with the Greek curriculum of general education (enkyklios [paideia]) called ‘liberal’ in Latin, but were concerned with the cultivation of virtue and freedom, setting the soul on its way towards virtue, the ultimate aim of which is to question the nature of the universe. Integration was definitely part of the liberal arts approach in Seneca’s view. And it had nothing to do with teaching to the text.

So what can we do that’s different?

Sound foundations can be acquired in a fun, inspiring way. And there’s nothing wrong with a combination of ambition, talent, and hard work.

It takes time, but it works. As long as it connects you to something that is eternal, meaningful, and life-affirming.

The tradition of liberal arts education has story at the heart of it. In fact, the Progynmasmata, which I use, and have based learning games on that appeal to students’ interests, include working with stories, fables, and sayings from the start.

That, and George Spencer-Brown’s Laws of Form, which makes classical logic far, far easier to work with than any other visual or symbolic approach we’ve thought up to date. The liberal arts curriculum should not be seen as a dead didactic dodo. The tradition should be respected and innovation within that tradition keeps it alive and up to date without affecting its essence.

Innovative Learning Approaches

TWB: Your book “Odyssey: Dynamic Learning System” showcases innovative learning approaches. Could you explain how you incorporate dynamic storytelling and interactive elements into your educational work?

LC: Going on an Odyssey Grid journey is exciting, inspirational. It liberates creativity.

The Odyssey Grid experience is designed to help people internalise knowledge and make it personally meaningful. It doesn’t stop there, though. It gets people excited about applying knowledge, not just memorising things.

Imagine you’re in a room, looking at a colourful grid of many different shapes spread out on a wall. There’s something intriguing about it – something almost magical. There are triangles, circles, squares, stars. Each has something on it – a word or diagram. There’s one shape of each colour … placed in a strange formation … what could the underlying pattern be? It’s as if each shape is a door or window to another world; the whole display a chocolate box for the mind – a magical carriage to take you on a journey through your imagination.

TWB: What impact do you hope these approaches will have on the learning experiences of your students and readers?

LC: Designed for teachers, trainers and facilitators, Odyssey Grid journeys are simple low-cost, highvalue ways to access the inspiration which lies at the core of the educational experience – making it easier for them to engage their students – and together, bring any subject to life.

Odyssey Grid journeys help students and educators find the inspirational magic which lies at the core of any successful educational experience – at all levels.

In short, Odyssey Grid journeys are designed to inspire.

Fascination with Storytelling and Structure

TWB: You’ve explored the Jewish oral storytelling tradition and studied George Spencer-Brown’s work. How have these influences shaped your own approach to storytelling and writing?

LC: Shonaleigh is unique in that she carries an estimated 4,000 stories in her and they are all ‘latticed’. We do not hear enough about latticing in discussions of how stories are structured, and yet, it is a ‘thing’. I write about her influence in Story and Structure where I also mention latticing. But really, you need to experience what Shonaleigh embodies for yourself.

As I mentioned previously, I could not have written Story and Structure without having come across George Spencer-Brown’s work, and my engagement with him provided the inspiration and intellectual challenge I was looking for to ‘crack the code of story’. I draw on his work daily – not just in my writing but in my everyday life as well.

TWB: Could you elaborate on how you apply insights from these traditions and studies to craft compelling narratives in your literary works?

LC: Story is a living thing. It needs to be respected.

That doesn’t mean we can’t invite it to play with us. In fact, story enjoys being involved.

We can easily walk past an empty crisp packet lying in our path.

And yet, that crisp packet has a story line of its own. It intersects with many people’s story lines, including mine, and now it has intersected with yours.

Literary Works and Publications

TWB: Your books cover a diverse range of topics, from storytelling and structure to history and fables. What themes or inspirations drive your writing, and how do you approach the creative process for each project?

LC: Usually there’s a provocation – a puzzling question that I can’t find a satisfactory answer for. I’m currently working on a book about poetry. I’d been meaning to extend the work I outlined in Story and Structure where I explained why popular poetic forms such as limericks and sonnets have the specific patterns that they have. You will find a lot out there about limericks – their form, their content, their social function, and Don Patterson has put forward a fascinating observation about the link between sonnet form and the golden section, but it remains an observation. If you want to go further; if you want to find out why it is that a limerick goes the way it does, and you will have been hard-pressed to find an answer up until recently.

Now, however, you will find a very precise answer in Story and Structure. There is a pattern of ebb and flow we experience in response to the metre and rhyme scheme that has a specific structure. That structure is also found driving a story structure which is very common. Once you see the common element, you can look at the types of stories which follow this structure, and the content and function of the limerick and marvel. There is much more work to do in this area. But you know what it’s like – there are a limited number of hours in a day and more things to do that I can find hours to complete them. What makes the difference is creative fire. And that often comes from a position I find provocative. The prod that set me on the 10-year journey that resulted in Story and Structure came from an author whose work I greatly admire: H Porter Abbott who claimed, in The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative that, ‘What is necessary for the story of Cinderella to be the story of Cinderella … is a question that can never be answered with precision.’ Why? How come? Did he have a crystal ball?

I found the challenge intriguing. It took me ten years, but Story and Structure outlines a precise answer as to what makes the story of Cinderella the story of Cinderella but what makes 18 story structures clearly identifiable. They all interrelate. And they all arise within us from our conscious being for a reason.

Recently, I came across a similar provocation in a book on poetry by another author whose work I admire, N M Gwynne. In the book, he comes down vehemently in favour of poetry which has a regular metre and follows a clear rhyme scheme. As for modern verse, he dismisses it unequivocally as substandard. Now, I have friends who are poets. Many choose to write in free verse, or experiment with form, and I very much admire their work. Gwynne’s extreme position made me wonder exactly when it was that metrical poetry came in and what it is about it that makes it so special, for him. If you trace the roots of poetry back far enough, you’ll find that the earliest poetry was not metrical. Nor did it rhyme. As to why the forms change, and what story structure has to do with it … there’s already a story to be told here and a new book is already unfolding.

“If you trace the roots of poetry back far enough, you’ll find that the earliest poetry was not metrical. Nor did it rhyme. As to why the forms change, and what story structure has to do with it … there’s already a story to be told here and a new book is already unfolding.”

– Leon Conrad

Award-Winning Book, “Story and Structure: A Complete Guide”

TWB: Congratulations on your book receiving the BREW Seal of Excellence and winning in the New Book and Nonfiction categories of the BREW Book Excellence Award, among other accolades! How does it feel to receive such recognition for your work?

LC: Thank you!

I’m deeply grateful and honoured that Story and Structure has received these awards. I’m also very grateful to Kajori Sherry Paul for her insightful review, thorough reading, and valuable feedback. I hope that, as a result, more people will find their way to the structures outlined in the book, and will benefit from the process it outlines.

TWB: Can you provide an overview of “Story and Structure: A Complete Guide” and how George Spencer-Brown’s six symbols are utilised to visualise story structures?

LC: Story and Structure is an invitation to you to totally rethink your idea of story. It reveals a clear relationship between individual story structures and the problems that give rise to them. Understanding this relationship makes it far easier and quicker for writers to follow the potential story lines that their characters could follow as a story unfolds. The system is flexible enough to allow for variation, but it also has inbuilt ‘safety rails’ that will help writers avoid time-consuming rewrites. The symbols are simple and visually intuitive. The patterns can be easily identified and checked, making it easier to spot plot holes. Understanding how steps can expand and contract gives writers an easy and effective tool they can use to pace stories in a robust way that keeps readers engaged. Last but not least, understanding that characters can both be trickster and have inner tricksters and tracing their story lines accordingly allows writers to develop a far greater command over the physical, emotional and intellectual aspects of their characters intersect; adding depth and richness to their work.

In short, the methodology makes it much easier for writers to distinguish between story structure (which unfolds at the time of the tale) and plot patterning (which unfolds at the time of the telling) and to work on each level at different stages of the writing process.

It’s easy to find out more. Visit my website to download a sample of the book which goes into the symbols in more detail. You can also join my mailing list to be the first to hear about tips, tricks, exclusive offers and new releases.

TWB: What inspired you to explore the link between storytelling and how we live our daily lives in this book, and what message do you hope readers take away from it?

LC: Imagine being in a state of flow where you are doing what you love, you’re ‘in the zone’, you’re focused, energised, and working at your optimum.

How would it feel like to tell that kind of story? Hearing about it wouldn’t be that exciting, right? But how would it feel like to live that kind of story? If you’ve experienced that state of being, when you’re in that state of flow, you’ll know how awesome it feels.

Events you go through in that state just flow forwards, just like they do in the story of creation as told in Genesis I: ‘In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth …’ There is no problem. There is no inciting incident.

I think that is the state we’re called to embody – and story shows us this possibility.

Just as the account in Genesis doesn’t flow forward unproblematically forever, so it would be difficult for us to sustain that state of flow for an extended length of time, but there is wisdom in story. And learning about story structures helps us avoid unproductive modes of tackling difficulties.

We all use story structures. We’re just not aware of the fact.

Knowing about them makes life so much easier! It really does help us go from ‘no’ to ‘flow’.

TWB: How do you believe your book distinguishes itself from other resources for storytelling and structure, and what unique insights or approaches does it offer to aspiring writers and storytellers?

LC: Most other approaches to analysing stories that I’ve come across look at the arc or shape of a narrative rather than looking at individual characters’ story lines and how they intersect. Focusing on each character’s story line and looking at how pairs of story lines intersect saves so much time at the editing stages. It helps writers avoid plot holes, and you can apply the methodology to your everyday life to help deal with inner tricksters or challenging problems more efficiently.

Most other writers who have looked at ways of analysing stories also focus on what I call ‘plot patterning’ – looking at how the tale unfolds at ‘the time of the telling’ rather than looking at how events follow on from one another in individual characters’ story lines in chronological order at the level of ‘story structure’ which unfolds at ‘the time of the tale’.

I don’t just outline 18 distinct story structures I’ve identified to date. I show how they interrelate as an integrated phenomenon that arises in and from our consciousness for a purpose. These interrelated structures, which are embodied structures we carry within us, arise for a reason: each of them links to and arises from a particular kind of problem; each one outlines the most efficient way to reach a solution to the kind of problem it links to. Sometimes these are problems we can solve ourselves (via the Quest structure), sometimes we need a Saviour character (which can be an internal saviour – a higher, metaphysical part of ourselves) in order for the problem to be solved (as in the Rags to Riches and Death and Rebirth structures).

Now, if that isn’t a life-hacking tool worth knowing about, I don’t know what is!

Story structures are not just tools we use to create compelling stories. They are part of life itself.

Finally, the book, for the first time ever to my knowledge, reveals the hidden link between poetic structure and story structure. We have poetic forms like limericks, sonnets, ghazals, and haikus for a reason. Each is based on a different story structure. And knowing that each story structure has a purpose has allowed me to shed new light on the deep, intrinsic purposes that each of these poetic structures contains within it. With this knowledge, you will never read a limerick or sonnet in the same way again.

“We have poetic forms like limericks, sonnets, ghazals, and haikus for a reason. Each is based on a different story structure. And knowing that each story structure has a purpose has allowed me to shed new light on the deep, intrinsic purposes that each of these poetic structures contains within it. With this knowledge, you will never read a limerick or sonnet in the same way again.”

– Leon Conrad

Literary Directions

TWB: Do you have plans to further explore or expand upon the concepts introduced in “Story and Structure: A Complete Guide” in future projects or publications?

LC: As I mentioned, there’s more to do in relation to mapping the story structures behind poetic form. At the Laws of Form conference in 2022, I spoke about how Spencer-Brown’s work relates to the different types of sentences we use in the English language, expanding the field there. People say there four types of sentences: statements, commands, questions, and exclamations. They teach this in schools, often linked to end punctuation marks. It’s very narrow-minded. We don’t use question marks when we think! Written sentences are only pale pointers that indicate a quality of thought – a ratio or relationship between the knower and the known. When you look at different sentence types like that, and map them to Spencer-Brown’s work, you realise that there are 7 distinct sentence types. Spencer-Brown’s work reinstates the optative (wish or prayer), it allows the interrobang sentence (You what, now?!) to be included, and most importantly of all, shows how important it is to include awestruck silence in the classification. Those times when you’re lost for words, when you feel you can’t possibly communicate the awesome totality of your experience, there’s definitely something going on in terms of a relationship between you as a knower and the ineffable mystery of the content of your thought. Just because you can’t put it into words doesn’t make it any less of a relationship.

TWB: How do you envision the ongoing relevance and impact of your book in the evolving landscape of storytelling and narrative structure?

LC: It’s high time we broke free from the dominance of the Hero’s Journey and other formulaic approaches to storytelling in the book and movie industries. While Story and Structure maps clear patterns of story, the 18 structures I’ve identified to date that are outlined in it are far more flexible than the Hero’s Journey (which, by the way, I see mapping to an overarching Call and Response Variation 2 structure, with nested substructures, as I outline in Chapter 18) and allow more interesting stories to unfold without restricting the natural flow of stories.

The work applies universally. Writers, storytellers, narrative therapists, anyone who uses narrative techniques in business settings, and the general reader who is simply interested in finding out more about story and how it works will all find something interesting and hopefully valuable as well in the book.

TWB: Could you tell us more about how the specific groups of people you mention could find your work particularly beneficial or innovative in shaping storytelling conventions they work with?

LC: In Story and Structure, storytellers and writers will find a bunch of reliable approaches to using story structure presented in an easy-to-read and easy-to-digest way that go deep so that if they feel stuck, they can get unstuck, feel inspired and get writing again.

Narrative therapists will find an easy checklist in it which is based on sound principles that they can go through quickly and efficiently to see how to solve a problem – theirs or a client’s – more clearly and efficiently.

Professionals will find structures clearly defined, with examples drawn from a range of contexts. They will also find an outline of how each of the structures might be applied most effectively in relation to solving a particular kind of problem. There is much that they will find useful in both their personal life and in their professional life.

I would also hope that the general reader would find something to delight them in it that will have the potential to feed their desire to learn about story and how it works so that they can be inspired to live their life more authentically, to flow with the current of story, and inspire others to do the same. ⭐

“In Story and Structure, storytellers and writers will find a bunch of reliable approaches to using story structure presented in an easy-to-read and easy-to-digest way that go deep so that if they feel stuck, they can get unstuck, feel inspired and get writing again.”

– Leon Conrad

For more information about the BREW Book, Blog, and Poetry Awards, click here.

Get a copy of Story and Structure by Leon Conrad by clicking here.

Connect with Leon Conrad through the following:

Social Media Handle: @leonconradstory

Linktree: https://linktr.ee/leonconradstory

Share your thoughts with us by commenting below!

What aspect of Leon Conrad’s diverse career and interests resonated with you the most?

How do you believe storytelling can be used as a tool for education and cultural preservation, as discussed by Leon?

In what ways do you incorporate elements of storytelling into your own creative pursuits, inspired by insights from the interview?

We look forward to hearing from you!

Announcements

😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh my, what I would give to listen to the Arabian Nights in Egypt! And I applaud the idea of coming up with less mechanical ways of learning. I remember Kajori’s review of this book. What an exciting interview!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Listening to the Arabian Nights in Egypt would be such a magical experience! And I agree, finding more organic and immersive ways of learning is truly valuable. Kajori’s review of this book must have been fascinating. It’s great to see such enthusiasm for innovative methods. Thanks for sharing your thoughts!

LikeLiked by 1 person