“I took the leap into full-time writing, using my experiences on the Appalachian Trail to shape stories and characters that come alive in my mind.”

– Kirk Ward Robinson

Kirk, thank you for joining us. To begin, could you introduce yourself and share a little about your background, what you do, and what drives your work?

Thank you for the opportunity. I’m Kirk Ward Robinson, and I’ve reached an age in which attempting to share my background would fill several memoirs. As concisely as I can, I was born and raised in the Rio Grande Valley of south Texas, went to high school in Houston, and university in El Paso. When I was six, my parents gave me an illustrated Funk & Wagnalls encyclopedia set, and I devoured every volume. The first book I selected and read on my own was Tom Sawyer. I was seven or eight by then, and decided that I needed to write my own book, which I did. It was titled The Pirates of Dublin and is, sadly, lost to history.

Nevertheless, this is where the writing began, followed by little stories and poems. It would have seemed that this was where my future lay but I allowed myself to become distracted by an abbreviated study of medicine, then all the things that happen when you marry and start a family at a young age. I went into business to support my family, did quite well, and twenty years slipped away.

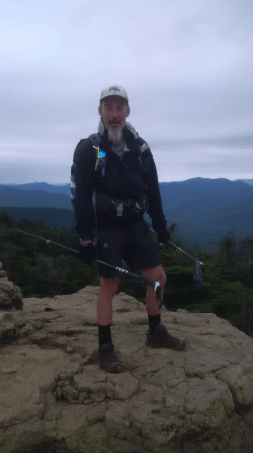

I thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail for the first time in 2001, and this was the turning point. Idealism can get away from you, and it did. With the kids grown, I retired every debt I had (and have taken on none since) and took the leap into full-time writing. I took a variety of odd jobs to pay the rent, jobs that became more rewarding than my business career, especially my time with the non-profits at Denali National Park and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area.

I thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail for the second time in 2008, and since then I haven’t needed to hold a regular job. Writing got me through. I purchased our ancestral farm in Tennessee a year later, restoring two 110-year-old Victorian houses and turning the former tobacco acres into organic orchards, where I specialize in our native pawpaw fruit.

What drives my work on the farm is the reward of preserving a family legacy, and lovingly tending more than one hundred trees, each one planted by me, and which have become somewhat like pets. What drives my work as an author, beyond the creative satisfaction of generating and sharing stories and characters that come alive in my mind, is to make up for lost time by writing at least one book per year. At this rate, I should be able to leave behind a decent body of work at my eventual demise.

You’ve hiked the Appalachian Trail multiple times. What has that experience taught you about endurance, perspective, and the way stories emerge from journeys?

I’ve written three books about this, and have struggled to explain it in every one of them.

The Appalachian Trail is brutal, probably the most difficult long trail in the world, although Vermonters might argue with that. There are days when you hate it, just hate it, but then you catch an unblemished view from a high peak, or rinse yourself indulgently clean in a brisk, clear pool, or watch a moose nudge her calf to safety in the woods, and you think, “You know, it wasn’t really that bad.”

But mostly it clears your mind. Nothing matters except the next water source, the next place to camp. No distractions. Many hikers wear their earbuds while hiking, or worse, play their jarring music aloud or else jabber on their phones along the way. I don’t. I don’t mind being alone in my head. As a matter of fact, I relish it. Meet a colorful person, of which there are many on the Appalachian Trail, and you now have a character for the next novel. Hike through an odd little town, and now an entire series of novels emerges. Paragraphs come to me fully formed. I can’t write them down quickly enough. And you have time, so much time. Time elongates. A day feels as if a week has passed, a week a month, and the months it takes to complete the hike feel as if you’ve been out there for years. Temporal perspectives make life seem endless. You understand intimately why Muir and Burroughs and Lummis and Thoreau were drawn to the wilderness again and again. And when you break your body down, lose your fat, and sweat out every free radical in your system, your mind takes on a surreal clarity. Dopamine is probably surging, and that might be part of it, but you feel really well. Complete. Whole. Capable of doing anything. No drug could possibly deliver this.

Your professional life has spanned several very different roles. How did these varied experiences shape the way you think and the way you write?

By becoming an inadvertent generalist, I’ve acquired skills across a broad range of life, from tuning bicycles and rebuilding carburetors, to interpreting the geology of the Colorado Plateau, to debits and credits and setting up a sound stage. But most of all, I’ve been able to work closely with a diversity of people, from corporate types to day laborers, and I’ve been able to do this all over the country and even the world. I’ve paid attention to how people really speak, their cadences, accents, and dialects, and I’ve incorporated this experience into the characters I create. It gives them authenticity. It gives them life.

Many readers know you through your writing, but what personal moments outside of publishing have most influenced the themes you explore in your books?

I was raised in the South. I’ve seen the belligerence and the gentility, the poverty and the hospitality. I’ve struggled to parse the unlettered accents, but then found myself taking on those tones as well, barely recognizing my own voice. I’ve been taken in from the pouring rain by Southerners who are living just below desperation, and have been fed from their limited cupboard. I’ve stood on the spongy autumn tundra of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as caribou moved past in herds larger than anything we’ve seen since the buffalo. I’ve stood trembling as a grizzly bear charged. I ran out of water in the Mojave and wouldn’t have made it but for the serendipity of a wily guy who was up to something nefarious but that didn’t seem important at the moment. I discovered unknown petroglyphs in a remote Arizona slot canyon, the enduring legacy of an anonymous hand a thousand years ago. I sat in Joan of Arc’s bedroom and pondered the mystery of her life. I sipped pastis in the French Alps until I passed out. I stood on Second Mesa and caught the basket a Hopi woman tossed me during the Basket Dance. I could go on, but it begins to sound as if I’m bragging.

Storytelling often highlights acts of resilience or transformation. How do you decide which stories deserve to be told, and how do you balance fact with interpretation?

All my stories derive from the kernel of an actual experience. In truth, I don’t choose the stories, they choose me, like a voice that demands to be heard. Into this I weave the characters, again derived from a kernel of reality. I take the opportunity to inject some social commentary, to explore some of the wrongs in our society, and resilience is a fact of my life. People can endure more than they know; I simply try to show them. As for fact and interpretation, I do careful research. I get the characters and settings as authentic as I can so that readers can suspend disbelief and relate. From then on, it’s the reader who does the interpreting. The same goes for my non-fiction. There are things we can’t know, so I tell the reader that, and if I wander off into a story that can’t be proved, but the story is just too juicy to leave out, I tell the reader that, too.

You’ve received recognition for your writing, including the Atlas of Stories Award from OneTribune Media. Could you share what these recognitions mean to you personally and professionally?

Both personally and professionally it’s gratifying. It’s been a long journey in which I’ve watched my youth slip away into memories that feel as if they belong to yesterday morning, and yet they are far in the past and the work goes on, and I could wonder if I would live long enough to garner any recognition for quality at all. I had a great-great-grandfather who was a doctor here in middle Tennessee. He was a life-saver for many of the old families of the region, practically revered, but he never had a formal medical education, as if he were merely a hobbyist who happened to save a few lives. In the last year of his life, 1871, Nashville Medical University awarded him an honorary sheepskin medical diploma. It hangs today on my wall behind museum glass, and I can reach through it and know that the latent recognition he received was probably one of the most inwardly validating events in his life. That’s the way I feel about the recognition I’m receiving now.

Exploration—whether through hiking, cycling, or research—seems central to your life. How does physical exploration connect with the creative exploration that fuels your work?

I touched on this a little earlier. First, I love to explore. The internet and smartphones have made the world seem small, but really it isn’t. The moment you think it is, try it on foot or bicycle. Suddenly that mile or two up the road for food or a cold beer seems like quite an investment, and when you’re on a ridge or mountaintop when a storm blows in, and there’s no one to save you…then you have to save yourself, and in the process learn what you’re capable of.

Second, journeying by human power slows the pace. You can observe and take more in. And the people you meet are mostly disarmed. You’re not part of a tour, you don’t overwhelm them. They treat you as an individual, not as an economic stimulator, and you learn things you wouldn’t nearly approach otherwise. You make lasting connections with total strangers, sometimes strangers in foreign countries, and that’s a rich, creative library to have in one’s head.

Third, when you break yourself down through extended exertion, when you’re truly vulnerable, you learn the truth about yourself and the people you meet. Some are dismissive, but most are caring in a way that leaves you humbled, and we can all use a little of that. And the exertion clears your mind. The pain of twinging knees and blistered heels is distant, not worthy of a place in the front of your mind. You know only what there is to know around you, and creativity fills the rest. Even here on my placid farm I still need to escape from time to time. The proximity of the Appalachian Trail makes that easy, and I will be embarking on Hike 5 soon. Can’t wait. Desperate for it.

Your books often highlight individuals who made an impact in their time. What criteria do you use when choosing the figures or stories you feature, and why?

It begins with a personal fascination and a yearning to learn more—and eventually connect in the most tangible way possible. When I stood on the Muralla Punica in Cartagena, Spain, I swore that I could feel Hannibal standing beside me. The same with Joan of Arc at the pyre in Rouen. I shed tears for someone who died six hundred years ago. George Washington I simply admire. Period. I’m not sure that there has been a leader like him since Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus 2,500 years ago. David Crockett because his myth touched the lives of people of my generation, especially in Texas and Tennessee, and I wanted to learn who he truly was as a person. Robert Gould Shaw because I nearly wept when I read some of his letters. Conflicted at first and then completely selfless, knowing in his gut that he wouldn’t survive but some things are larger than a single life. Crazy Horse because readers needed to understand that he wasn’t some savage, but a breathing, caring man who fought hopelessly for his people. Matthew Henson because his feat was phenomenal—phenomenal even now but especially then, and he needs to be remembered. Rachel Carson because she saved the bald eagle. I have camped among hundreds of them, enraptured as I watched them preen and waft on the thermals and swoop salmon out of Kachemak Bay, and I owe it all to Rachel. Also, she set in motion a movement that has saved us whether some politicians accept that or not, and I suspect that she’s been forgotten in modern times. Karen Silkwood for the same reason, an ordinary person with all kinds of shortcomings, seeming of limited character, but she threw herself at the monolith of the nuclear industry and possibly spared us from disaster, and again is probably not well-remembered today.

In your view, how can stories about courage or resilience be useful to people in everyday life, far removed from dramatic historical events?

Who is not proud of their own courageous act, whether large or small? Whose self-esteem would not be buoyed by stepping beyond the common? Who wants to think that their neighbors or co-workers are more courageous, are elevated higher because of it? We face so many challenges, especially today, rehashing the same issues that have been going on all my life. It would be gratifying to put at least one of these issues to bed once and for all. In every one of these issues that have been fought historically, if you look back you will find a courageous person who made a difference. It’s the absence of demonstrable courage that allows this regression. If more people took courage and stood up, the forces of regression would have no power. Courage can begin as a small act in an everyday life, something not tied to any greater movement. But that courage will be noticed. It’s infectious. It will be magnified and emulated, with altruism as the root. If my stories are written well enough, and connect well enough, perhaps a few more of the courageous will step forward and we can stem this tide of stagnation.

What advice would you give to readers or aspiring writers who want to pursue projects that combine personal passion with a broader cultural or historical lens?

Get out and touch it. Transcend the present. Feel the weight of history taking your breath. Don’t ignore that passion, write it down. I keep journals throughout the house, and will scrawl a line here and there as I pass through a room. When I’m out working the farm, I keep a journal in my back pocket. I keep a journal when I hike, when I cycle. I have dozens and dozens of them now, notated in red ink when I find a good line that I would have forgotten otherwise. Eventually these lines accumulate to outline an entire book. Also, if that idea comes to you just as you’re falling asleep, force yourself up and write it down. Believe me, otherwise you’ll forget it by morning. And most important—read. Read as much as you can. Find the time. Make the time. A book is a university in your hands. You won’t learn more elsewhere.

If you were to write your bio in your own words, what would you say? What legacy do you hope to leave?

My oldest son asked me if I would ever write an autobiography. I told him no, and for the same reasons that Carlton uses in The Appalachian. Some things, especially personal things, need to be buried by time, otherwise they weight future generations or else become trivialities to gossip about. I told him that my Notes from the Field series was the closest I would ever come to an autobiography. My legacy is preserving my family’s ancestral home for at least one more generation, two sons, and what I hope becomes a significant body of work. If I achieve any notoriety, readers can glean my books and find my autobiography there.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

“My legacy is preserving my family’s ancestral home and leaving behind a significant body of work that readers can explore and connect with.”

– Kirk Ward Robinson

Links

- Know more about the BREW Book, Blog, and Poetry Awards here

Share Your Insights

- Which part of Kirk Ward Robinson’s journey resonated with you most?

- How do you draw inspiration from your own experiences for creative projects?

- What lessons about resilience or courage stood out to you in the interview?

Alignment with the UN SDGs

- Promotes lifelong learning and personal growth through storytelling and reading (SDG 4).

- Highlights resilience and courage in overcoming challenges (SDG 3).

- Encourages responsible stewardship of land and heritage (SDG 15).

Other Highlights

Looking for something?

Type in your keyword(s) below and click the “Search” button.

Helpful Shortcuts

More Stories

Print and Digital Magazine

About Us

The World’s Best Magazine is a print and online publication that highlights the extraordinary. It is your passport to a universe where brilliance knows no bounds. Celebrating outstanding achievements in various fields and industries, we curate and showcase the exceptional, groundbreaking, and culturally significant. Our premier laurels, The World’s Best Awards, commend excellence through a unique process involving subject matter experts and a worldwide audience vote. Explore with us the pinnacle of human achievement and its intersection with diversity, innovation, creativity, and sustainability.

We recognise and honour the Traditional Owners of the land upon which our main office is situated. We extend our deepest respects to Elders past, present, and emerging. We celebrate the stories, culture, and traditions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders from all communities who also reside and work on this land.

Disclaimer: The World’s Best does not provide any form of professional advice. All views and opinions expressed in each post are the contributor’s own. Whereas we implement editorial policies and aim for content accuracy, the details shared on our platforms are intended for informational purposes only. We recommend evaluating each third-party link or site independently, as we cannot be held responsible for any results from their use. In all cases and with no exceptions, you are expected to conduct your own research and seek professional assistance as necessary prior to making any financial, medical, personal, business, or life-changing decisions arising from any content published on this site. All brands and trademarks mentioned belong to their respective owners. Your continued use of our site means you agree with all of these and our other site policies, terms, and conditions. For more details, please refer to the links below.

About | Advertise | Awards | Blogs | Contact | Disclaimer | Submissions | Subscribe | Privacy | Publications | Terms | Winners

The World’s Best: A Magazine That’s All About What’s Great | theworldsbestmagazine.com | Copyright ⓒ 2022-2026

Let’s connect

Discover more from The World's Best

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.